Obituaries

On September 24, 1923, William Ellis passed the final border, that between life and death. He was only 59 at the time of his demise, leading one to wonder whether the stress of his double life, with its constant need to conceal so much of his existence from all but his closest family and friends, took a toll on his health.

Ellis passed away in the American Hospital in Mexico City—one of the rare moments when Ellis, who had carefully avoided the American colony in Mexico City during the previous decades in the Mexican capital, engaged with other Americans south of the border. Yet even in death, Ellis managed to remain an enigma. Rather than being buried in the American Cemetery in Mexico City or in a Mexican graveyard, he was instead interred in an unmarked grave in the Panteón Español (Spanish Cemetery).

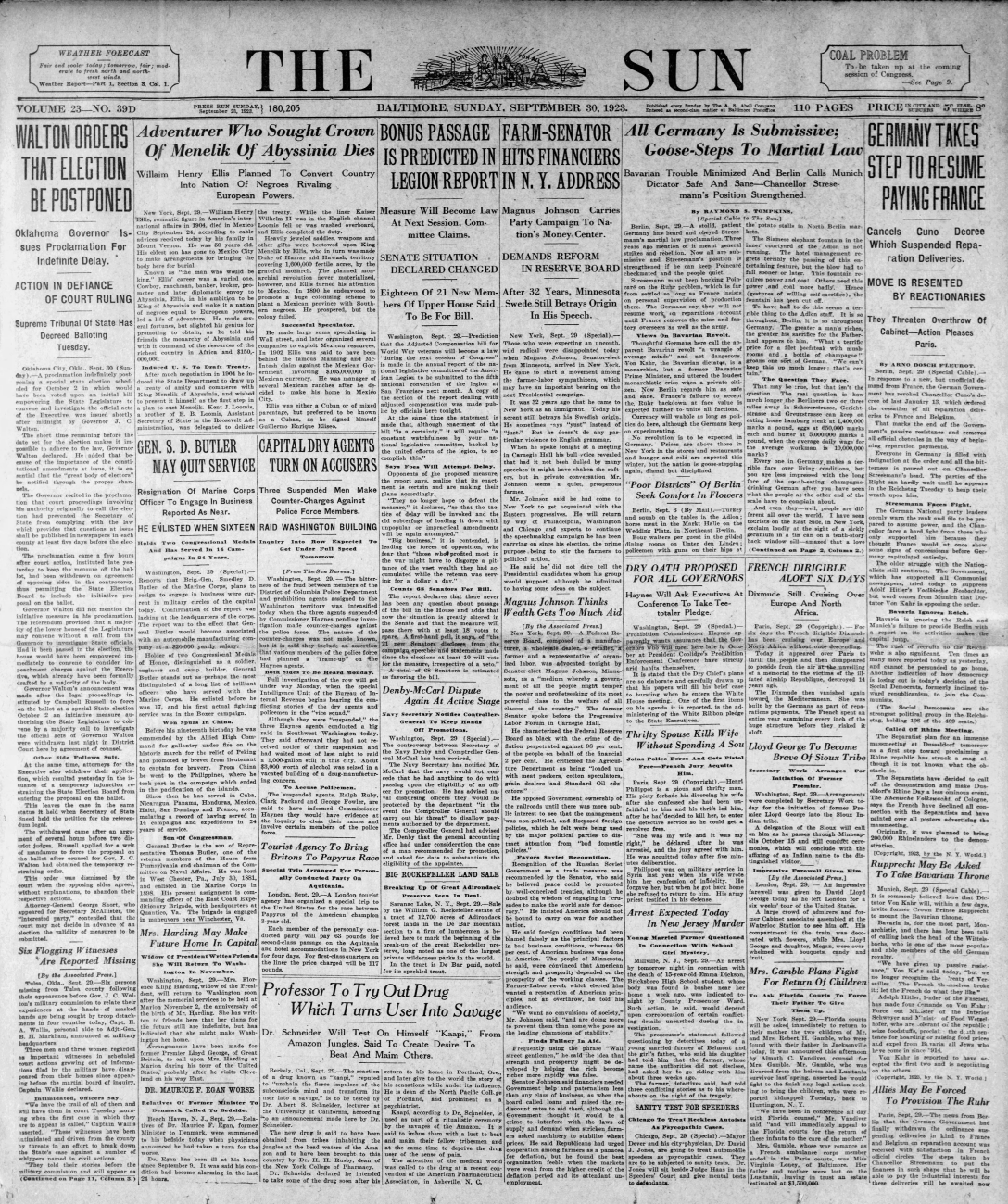

WH Ellis’s grave in Mexico City

News of Ellis’s death was first published in the United States by the Mount Vernon Argus, the paper based in the almost all-white suburb outside New York City were Ellis and his family had lived for almost two decades. The Argus did little to dig beneath the image that Ellis had taken such care to cultivate during his time in Mount Vernon, declaring that Ellis was also known as “G[uillermo] E[nrique] Eliseo” and that he had been born “near the Mexican border” to “Carlos and Margarita (Nelsonia) Ellis.” The New York Times in the obituary it printed a few days later on September 30, 1923 also reinforced the persona that Ellis had crafted over his time in New York, stating that Ellis was a “broker and promoter of this city [Manhattan] and Mexico.”

But with Ellis’s passing, the Black press finally felt free to disclose what had apparently long been an open secret in the African American community: the Mexican/Cuban businessman known to most on Wall Street as Guillermo Eliseo had, in fact, begun life as the African American named William Ellis. Perhaps the first African American newspaper to make this information public was the New York Age in early October, 1923, although the information was soon disseminated by other prominent organs of the Black press such as the Chicago Broad Axe and the Chicago Defender. (Examples of these latter obituaries can be found in the attached documents as can the obituary from the New York Times as well as obituaries from Arizona, Ohio, Wisconsin, and other parts of the country.)